In a week talking about art asking questions, it's important that we also remember to ask questions of our art -- why we do it, what it means for us to be artists. These practicing artists, coming from all different backgrounds and influences, summed this up better than I ever could. Here were some of my favorite parts:

|

Gina Gibney's choreography. (Andrzej Olejniczak/Gina Gibney)

|

I make art for a few reasons. In life, we experience so much fragmentation of thought and feeling. For me, creating art brings things back together.

For me, making work is almost like keeping a journal. Giving that to someone else—as a kind of gift through live performance—is the most meaningful aspect of my work.

|

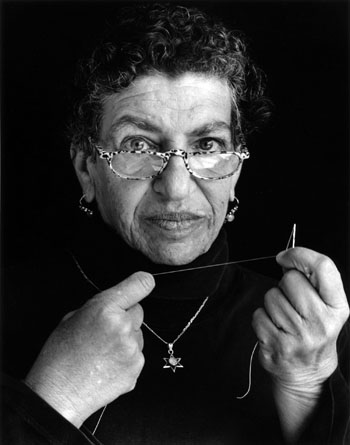

| A portrait by Judy Dater. |

I like expressing emotions—to have others feel what it is I’m feeling when I’m photographing people. [...] I think photographing people is, for me, the best way to show somebody something about themselves—either the person I photograph or the person looking—that maybe they didn’t already know. [...] I feel like I’m attending to people when I’m photographing them.

Pete Docter:

I make art primarily because I enjoy the process. It’s fun making things.

And I’m sure there is also that universal desire to connect with other people in some way, to tell them about myself or my experiences. What I really look for in a project is something that resonates with life as I see it, and speaks to our experiences as humans. That probably sounds pretty highfalutin’ coming from someone who makes cartoons, but I think all the directors at Pixar feel the same way. We want to entertain people, not only in the vacuous, escapist sense (though to be sure, there’s a lot of that in our movies too), but in a way that resonates with the audience as being truthful about life—some deeper emotional experience that they recognize in their own existence. On the surface, our films are about toys, monsters, fish, or robots; at a foundational level they’re about very universal things: our own struggles with mortality, loss, and defining who we are in the world.

|

An image from "The Problem of Possible

Redemption 2003," staged at the 2004 Whitney Biennial in New York. (Harell Fletcher)

|

By the time I got to graduate school, I was not so interested in making more stuff, and instead started to move into another direction, which these days is sometimes called “Social Practice.” [...] I think of it as the opposite of Studio Practice—making objects in isolation, to be shown and hopefully sold in a gallery context. Most of the art world operates with this Studio Practice approach. In Social Practice, there is more of an emphasis on ideas and actions than on objects; it can take place outside of art contexts, and there is often a collaborative or participatory aspect to the work. So back to the question why I make art. In my case, the projects that I do allow me to meet people I wouldn’t ordinarily meet, travel to places I wouldn’t normally go to, learn about subjects that I didn’t know I would be interested in, and sometimes even help people out in small ways that make me feel good. I like to say that what I’m after is to have an interesting life, and doing the work that I do as an artist helps me achieve that.

|

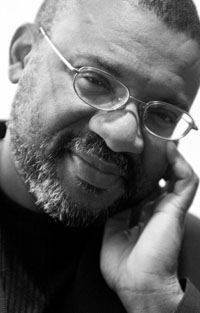

| Kwame Dawes |

I’m trying to capture in language the things that I see and feel, as a way of recording their beauty and power and terror, so that I can return to those things and relive them. In that way, I try to have some sense of control in a chaotic world.

I want to somehow communicate my sense of the world—that way of understanding, engaging, experiencing the world—to somebody else. I want them to be transported into the world that I have created with language.

James Sturm:

I like the question “Why Do You Make Art?” because it assumes what I do is art. A flattering assumption. [...] Whatever the reason, an inner compulsion exists and I continue to honor this internal imperative. If I didn’t, I would feel really horrible. I would be a broken man.

KRS-One:

I was born this way, born to make art, to make hip hop. And I think I’m just one of the people who had the courage to stay with my born identity. Hip hop keeps me true to myself, keeps me human. Hip hop is the opposite of technology. Hip hop is what the human body does: Breaking, DJing, graffiti writing. [...] The manipulation of technology is what humans do, that’s art.

Or take graffiti writing. Put a writing utensil in any kid’s hand at age two or three. They will not write on a paper like they’ll later be socialized to do, they will write on the walls. They’re just playing. That’s human.Now go read the rest of the article, get inspired -- then come back and tell us why YOU make art!

No comments:

Post a Comment